As usual, the following post is available in podcast form at www.medonthego.podbean.com. Feel free to also check out our Facebook page at www.facebook.com/drolimedonthego/. If you enjoy and wish to support our work please visit www.patron.podbean.com/medonthego for more details.

By definition, peptic ulcer disease refers to focal defects

in the mucosa of the stomach and duodenum that penetrate the muscularis mucosal

layer, resulting in scarring (defects superficial to the muscularis mucosa are

erosions and do not cause scarring.

(Quick review of anatomy: the GIT contains four layers. The

inner most layer is the mucosa—which includes epithelium, lamina propria, and

muscularis mucosa—followed the sub mucosa, muscularis propria, and adventitia.

Helicobacter

pylori, previously Campylobacter

pylori, is a gram-negative, microaerophilic bacterium found usually in the stomach. It was identified in 1982 by

Australian scientists Barry

Marshall and Robin

Warren, who found that

it was present in a person with chronic gastritis and gastric

ulcers, conditions not

previously believed to have a microbial cause. It is also linked to the

development of duodenal ulcers and stomach cancer. More than 50% of the world's population harbor H. pylori in

their upper gastrointestinal tract, more common in developing countries. However, over 80% of

individuals infected with the bacterium are asymptomatic.)

Etiology

|

|

Duodenal

|

Gastric

|

|

H. Pylori

|

90%

|

60%

|

|

NSAID

|

7%

|

35%

|

|

Idiopathic

|

15%

|

10%

|

|

Physiologic (stress-induced)

|

<3%

|

<5%

|

|

Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome

|

<1%

|

<1%

|

(Another brief review: Zollinger-Ellison syndrome is a rare condition in which one

or more tumors form in your pancreas or the upper part of your small intestine

(duodenum). These tumors, called gastrinomas, secrete large amounts of the hormone

gastrin, which causes the stomach to produce too much acid.)

Ulcers not related to H. Pylori or NSAIDs are becoming more

commonly recognized; these include CMV, cirrhosis of the liver, COPD, chronic

renal failure, ischemic and idiopathic causes. Cigarette smoking has been

linked to peptic ulcer disease; smoking not only impairs healing but also increases

the risk of ulcers, complications, and death. In contrast to popular belief,

alcohol consumption damages the gastric mucosa but does not cause ulcers.

Clinical presentation

·

Dyspepsia

o

Most common presentation

o

Only 5% will have ulcers—most have functional

disease

o

Can present with complications

§

Bleeding—most common! 10% The bleeding can be severe

if from the gastroduodenal artery

§

Perforation (usually from anterior ulcers) 2%

§

Gastric outlet obstruction 2%

§

Posterior inflammation (penetration) 2% and can

cause pancreatitis

·

Duodenal ulcers

o

History alone is very similar to that of

functional dyspepsia

o

6 classical features

§

Epigastric pain: may localize to tip of xiphoid

§

Burning sensation

§

Develops 1~3 hours after meals

§

Relieved by eating and antacids

§

Interrupts sleep

§

Periodicity (tends to occur in clusters over a

week with subsequent periods of remission)

·

Gastric ulcers

o

More atypical symptoms

§

Dull aching pain, often right after eating.

§

Eating will not relieve pain!

§

Dyspepsia or acid reflux

§

Episodes of nausea

§

A noticeable loss of appetite

§

Unplanned weight loss

o

A BIOPSY REQUIRED to rule out malignancy (whereas

duodenal ulcers are rarely malignant.)

Investigations

·

Endoscopy (most accurate)

·

Upper GI series

·

H. Pylori tests

·

Fasting serum gastrin measurement if

Zollinger-Ellison syndrome suspected—but most common cause of elevated serum

gastrin level is atrophic gastritis.

Treatment

·

Specific management depends on etiology

·

Eradicate H pylori if it is present

·

Stop NSAIDs if possible

·

Start proton-pump inhibitors PPI

o

Inhibits parietal cell H+/K+-ATPase pump which

secretes acid

o

Will heal most ulcers even if NSAIDs are

continued

o

Other medications such as histamine

H2-antagonists are less effective

·

Stop smoking

·

No diet modification required but some people have

fewer symptoms if they avoid coffee, alcohol, and spices

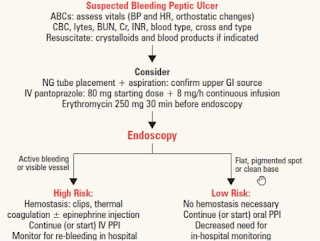

Management of bleeding peptic ulcers

·

Endoscopy (OGD) to explore upper GI tract

·

IV pantoprazole continuous drip

·

Evaluate risk of rebleeding/continuous bleeding

(most ulcers will stop bleeding spontaneously

o

Clinical risk factors: increased age (>60),

bleeding diathesis, history of peptic ulcer disease, comorbid disease,

hemodynamically unstable (transfusion required)

o

Endoscopic signs of recurrent bleeding are more

predictive than clinical risk factors: active bleeding, visible vessel, clots,

red spots

o

If high risk, consider ICU admission

H. Pylori-induced peptic ulceration

Pathophysiology

·

H. Pylori are Gram-negative flagellated rod that

resides within the gastric mucosa, causing persistent infection and

inflammation.

·

Acid secreted by parietal cells (stimulated by

vagal acetylcholine, gastrin, histamine) is necessary for most ulcers

·

No satisfactory theories of how H. pylori causes

ulcers, but pattern of colonization correlates with outcome

o

Gastritis only in antrum (15% of patients) and

high gastric acid are associated duodenal ulcer and may progress to gastric

metaplasia of duodenum where ulcer forms.

o

Gastritis through stomach (“pangastritis”—85% of

patients) and low gastric acid are associated with stomach ulcer and cancer.

Epidemiology

·

H. Pylori is found in about 20% of all Canadians

·

Highest prevalence in those raised during the

1930s

·

Infection most commonly acquired in childhood,

presumably by fecal-oral route

·

High prevalence in developing countries,

particularly in those of low socioeconomic status (poor sanitation and

overcrowding)

Outcome

·

Non-erosive gastritis in 100% of patients but asymptomatic

·

Peptic ulcer in 15% of patients

·

Gastric carcinoma and mucosal associated

lymphomatous tissue (MALT) lymphoma in 0.5% of patients

·

Most are asymptomatic but still worthwhile

eradicating to lower future risk of peptic ulcer/gastric malignancy and prevent

spread to others (mostly children <5 years)

Diagnosis

·

Non-invasive

o

Urea breath test

§

90~100% sensitivity

§

89~100% specificity

§

Can be falsely negative when on PPI therapy

o

Serology

§

88~99% sensitivity

§

89~95% specificity

§

Can remain positive after treatment

·

Invasive (requires endoscopy)

o

Histology

§

93~99% sensitivity

§

95~99% specificity

§

Gold standard!

§

Can be falsely negative when on PPI therapy

o

Rapid urease test (on biopsy)

§

89~98% sensitivity

§

93~100% specificity

§

Rapid

o

Microbiology culture

§

98% sensitivity

§

95~100% specificity

§

Research only

Treatment: H. Pylori eradication

·

Triple therapy for 7~14 days

o

PPI bid + amoxicillin 1g bid + clarithromycin

500mg bid

o

Becoming less successful as prevalence of H.

pylori clarithromycin-resistance on the rise

·

Quadruple therapy for 10~14 days now recommended

o

PPI bid + bismuth 525mg qid + tetracycline 500mg

qid +metronidazole 250mg qid

·

Levofloxacin can replace metronidazole or

tetracycline

·

Sequential therapy

o

5 days of PPI bid + amoxicillin 1g bid

o

6~10 days of PPI bid + clarithromycin 500mg bid,

tinidazole 500mg bid (generally substitute with metronidazole as tinidazole is

not available in Canada)

·

5~15% are resistant to all known therapies

NSAID-induced ulceration

NSAID use causes gastric mucosal petechiae in virtually all

erosions in most people and ulcers in some people (25%); erosions can bleed,

but usually only ulcers cause significant clinical problems. Most NSAID ulcers

are clinically silent—dyspepsia is as common in patients with ulcers as

patients without ulcers; NSAID-induced ulcers characteristically present with

complications such as bleeding, perforation, and obstruction. NSAIDs more

commonly cause gastric ulcers than duodenal ulcers. NSAID use may exacerbate

underlying duodenal ulcer disease.

Pathophysiology

·

Direct: erosions/petechiae are due to local

effect of drug on gastric mucosa

·

Indirect: systemic NSAID effect (intravenous

NSAID causes ulcers, but not erosions due to inhibition of mucosal

cyclooxygenase, leading to decreased synthesis of protective prostaglandins,

thus leading to ulcers

Risk factors for NSAID-induced peptic ulcer

·

Previous peptic ulcers or upper GI bleeding

·

Age >65

·

High dose of NSAID/multiple NSAIDs being taken

·

Concomitant corticosteroid use

·

Concomitant cardiovascular disease/other

significant disease

Management

·

Prophylactic cytoprotective therapy with PPI is

recommended if any of the above risk factors exist concomitantly with ASA/NSAID

use

·

Lower NSAID dose or stop all together and

replace with acetaminophen

·

Combine NSAID with PPI or misoprostol (less

effective) in one tablet

·

Enteric coating of aspirin provides minor

benefit since this decreases incidence of erosion, not incidence of ulceration

Stress-induced ulceration

Defined as ulceration or erosion in the upper GI tract of

ill patients, usually in ICU (the stress is physiologic not psychologic),

stress-induced lesions are most commonly in the fundus of the stomach. The

pathophysiology is unclear; it likely involves ischemia and may be cause by CNS

disease and acid hypersecretion.

Risk factors include:

·

Mechanical ventilation—most important

·

Anti-coagulation

·

Multi-organ failure

·

Septicemia

·

Severe surgery/trauma

·

CNS injury

·

Burns involving more than 35% of body surface

|

Curling’s ulcer

|

Cushing’s ulcer

|

|

Acute peptic ulcer of the duodenum resulting as a

complication from severe burns when reduced plasma volume leads to ischemia

and cell necrosis (sloughing) of the gastric mucosa.

Think: BURN from a CURLING iron!

|

Peptic ulcer produced by elevated intracranial pressure

(may be due to stimulation of vagal nuclei secondary to elevated ICP which

leads to increased secretion of gastric acid)

|

Clinical feature is painless upper GI bleeding. Treatment

includes prophylaxis with gastric acid suppressants to decrease the risk of

upper GI bleeding. PPI most potent but may increase risk of pneumonia; H2

blockers less potent but less likely to cause pneumonia. In active bleeding

ulcer the treatment is the same as covered above in peptic ulcer disease but

often less successful.