As usual, today's post is also available in podcast form. Look for "Med On The Go" on Podbean, iTunes, and Google Play. Subscribe so you'll never miss an episode! Also feel free to check out our Facebook page at www.facebook.com/drolimedonthego. If you enjoy my work, please consider supporting me--visit www.patron.podbean.com/medonthego for more details!

Onto today's topic:

While eating gluten-free can be just a lifestyle choice, for

those with coeliac disease it is not a choice but a necessity. Now, perhaps

with the combination of advanced medicine, wheat consumption, and migratory

patterns, the diagnosis and worldwide distribution of coeliac disease is on the

rise. So let’s get to know one of the most common genetic diseases: coeliac

disease.

Essentially coeliac disease is an abnormality of the small

intestine mucosa due to a reaction to gluten, a protein found in cereals. As

mentioned previously, it is a genetic disease; HLA-DQ2 (chromosome 6) is found

in 80~90% of patients compared with 20% in the general population. Coeliac

disease can also be associated with HLA-DQ8 (up to 40% of Caucasians carry the

HLA alleles but will never develop the disease.) When gluten is digested, it is

broken down into gliadin, which is the toxic factor to those with coeliac

disease—the body attacks the gliadin and in the process damages its own villi;

interestingly, unlike other autoimmune diseases, coeliac disease is the only

autoimmune disease in which the antigen is actually recognized. However, like

other autoimmune diseases, when you get one, you tend to get more than

one—coeliac disease is associated with other autoimmune diseases, especially

Sjogren’s disease and thyroid disease.

Once thought to be a disease only affecting Caucasians,

coeliac disease is now diagnosed worldwide. It is more commonly found in women.

Family histories reveal that 10~15% of first-degree relatives will also be

affected. Coeliac disease can present any time from infancy (when cereals

introduced—peak presentation) to the elderly; it can lay dormant until

triggered by certain events (immigration or sickness or other).

A classic presentation of coeliac disease would be the

combination of diarrhea, weight loss, anemia, symptoms of vitamin/mineral

deficiency, and failure to thrive in infants. More common current presentations

include bloating, gas, and iron deficiency. The symptoms improve when gluten is

eliminated from the diet and deteriorate when gluten is reintroduced. Because

the disease is usually more severe in the proximal bowel, iron, calcium, and

folic acid deficiency is more common (as these are absorbed proximally) than

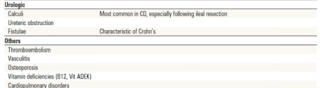

B12 deficiency (absorbed in ileum). Coeliac disease can be associated with

non-GIT conditions such as dermatitis herpetiformis skin eruptions (large

vesicles with yellow liquid), epilepsy, myopathy, depression, paranoia,

infertility, bone fractures, or metabolic bone disease.

The golden standard of diagnosis is small bowel mucosal

biopsy (usually from duodenum) showing increased intraepithelial lymphocytes

(earliest pathologic finding), crypt hyperplasia, and villous atrophy (which

can also be seen in small bowel overgrowth, Crohn’s disease, lymphoma, Giardia,

and HIV); however, serological tests can also be performed. Serum anti-tTG (tissue

transglutaminase) antibody, IgA, is 90~98% sensitive, 94~97% specific. IgA

deficient patients have false-negative anti-tTG; therefore, measure serum IgA

concomitantly via serum quantitative protein electrophoresis and incorporate

serum testing tTG and/or DGP (deamidated gliadin peptide) IgG in IgA

deficiencies. There will be evidence of malabsorption; these can be either

localized or generalized, such as steatorrhea, low levels of ferritin/iron

saturation, iron, calcium, albumin, cholesterol, carotene, and vitamin B12.

Consider CT enterography to visualize small bowel to rule out lymphoma.

Gluten-free diets should not be started before serological

tests and biopsy. Gluten is found in barley, rye, some oats, and wheat (mnemonic

BROW) and should be avoided in the patient’s diet; however, sometimes oats are

allowed if it is grown in soil without cross-contamination by other grains.

Rice and corn flour are acceptable. Supplementary of iron, folate, and other

vitamins/minerals should be added as necessary. If there is a poor response to

diet change, consider alternate diagnosis, concurrent disease (e.g. microscopic

colitis, pancreatic insufficiency), development of intestinal

(enteropathy-associated T-cell) lymphoma (symptoms include abdominal pain,

weight loss, and palpable mass), or development of diffuse intestinal

ulceration, characterized by aberrant intraepithelial T-cell population

(precursor to lymphoma).

Coeliac disease is associated with increased risk of

lymphoma, carcinoma (e.g. small bowel and colon; small increase compared with

general population), and autoimmune diseases. The risk of lymphoma may be

lowered by gluten-free diet.